This guest blog post comes from Piatti Tennis Center strength and condition coach Leandro Mosconi:

Every athlete must know their profession and themselves. Self-knowledge is key to understanding what recovery techniques and routines work best for you. It is important to start experimenting with different techniques from a young age to identify what suits you better depending on the context. This is because growth and improvement are more important at a young age than the result itself. Similar to the warm-up routine, a cool-down routine can also have a positive impact on an athlete’s mental health. Having a post-match routine can influence an athlete’s discipline and overall mental state. As I mentioned in my previous article, developing proper habits can lead to a better quality of life and less stress. Eating well, sleeping well, and behaving professionally lead to positive outcomes while doing the opposite leads to negative outcomes and the formation of bad habits. Recovering well is part of this discipline and dedicating time to yourself after a workout, for example, stretching, can have long-term benefits.

In this article, I will discuss the crucial role of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in the recovery process. I will also categorize common recovery techniques used by athletes based on their context.

It’s all about energy

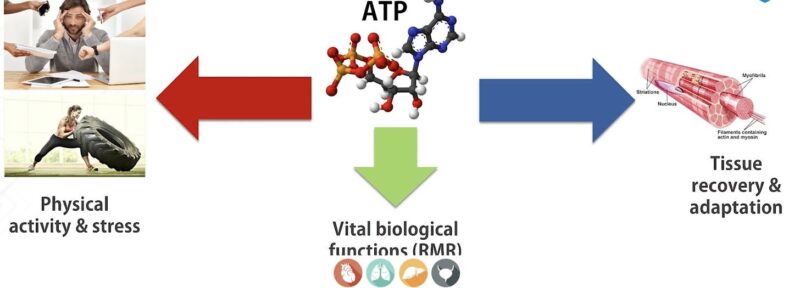

Physical activity and recovery are dependent on the energy developed and used by our body. The energy currency of the body is called Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which is directed by the autonomic nervous system (ANS) into three categories (Figure 1): vital body functions, physical activity and mental stress, and tissue creation and adaptation.

The first principle of thermodynamics states that energy is neither created nor destroyed, and all organs of our body require energy for their functioning. The sum of the energy consumed by the organs of the body is called Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) which represents between 60% and 75% of an individual’s total metabolism. The RMR is a constant as it is essential for staying alive. When we perform physical activities, the energy is distributed towards the muscles, heart, and brain because they require ATP to function and maintain energy balance. Additionally, mental stress leads to greater energy consumption. The human body requires constant tissue construction and remodeling, especially after physical stress such as training, and this involves a mobilization of ATP towards this third category.

Figure 1: This graph shows the energy distribution (ATP) dictated by the ANS

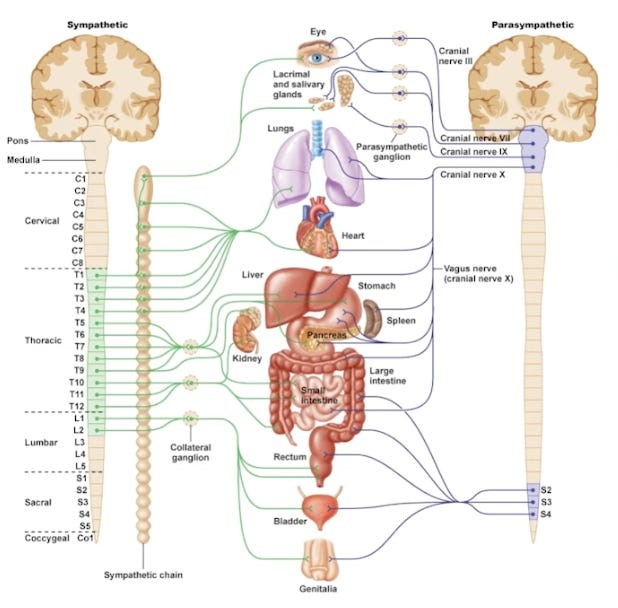

The ANS manages the flow of energy through the release of hormones by certain organs and structures that are activated and inhibited. Hormones create changes in our body and break the homeostasis or balance of our system (Figure 2). The ANS reacts to the environment by activating two main large systems present within it: the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The fight or flight response system, or the sympathetic system, is activated in reaction to a “dangerous” and alert environment, making our body ready to flee or fight. The parasympathetic system acts in the opposite way and is also called rest and recovery. It reduces the heart rate, and blood pressure, and stimulates digestion.

Figure 2: The ANS is connected to several organs in the body. When stimulated, these organs release hormones in response.

The ANS therefore, through the sympathetic and parasympathetic system, has the role of distributing the energy in our organism more in the three categories mentioned previously which are: vital functions, physical activity and mental stress, and recovery and adaptation. The sympathetic system moves energy more towards physical activity, perhaps removing it from recovery and adaptation, while the parasympathetic system does the opposite. The human body continues to fluctuate more towards one situation than another based on the surrounding environment, through the activation of structures that create hormonal stress and a destruction of homeostasis.

To improve an athlete’s recovery, there are two ways: either reduce the inflammatory state or facilitate recovery and stimulate adaptation. By reducing the inflammatory state, high levels of fatigue caused by high frequencies of training and matches are reduced, which in turn reduces muscle function and performance. Fatigue is a complex phenomenon caused by a combination of central and peripheral factors. On the other hand, to create a new adaptation, the training session has the purpose of breaking homeostasis and consequently increasing the inflammatory state. It is only through inflammation that adaptation and subsequent improvement can occur. Therefore, to promote recovery, adaptation can be facilitated or the inflammatory state can be blocked. The benefits of adaptation and improvement while blocking the inflammatory state result in reduced recovery times and greater “readiness” and short-term performance. The approach to take, however, depends on the context. During the off-season or periods in which adaptation and improvement are sought, it would be more correct to facilitate recovery and not reduce the inflammatory state. Conversely, during the in-season or periods in which fast recovery is a priority, it is necessary to reduce the inflammatory state to enter the field with better performance and not under fatigue.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) can stimulate adaptation or reduce the inflammatory state through the participation of the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems, respectively. There are techniques and methods that will activate one system more than the other. The methods that stimulate adaptation and direct energy more towards tissue remodeling and construction are those that activate the parasympathetic system. These techniques include meditation, stretching, soft tissue therapy, hot water therapy, deep water floating, swimming, mindfulness, and sauna. In contrast, the sympathetic system can be activated to reduce the inflammatory state and pain through techniques such as intensive deep tissue therapy, cold water immersion, contrast therapy, and ice baths. These techniques can be particularly useful in tennis when competing on consecutive days, or even between morning and afternoon matches.

Knowing yourself and your athletic type is crucial to determining the best recovery method for you. Athletes can be divided into two categories: sympathetic-driven and parasympathetic-driven. The former can activate easily but have difficulty entering a state of recovery, leading to an above-average inflammatory state. Recovery techniques that stimulate the parasympathetic, such as meditation and hot water therapy, are recommended for them. On the other hand, athletes who are parasympathetic-dominant have difficulty activating and need techniques that stimulate sympathetic activity, especially between matches on the same day. There is no clear division between these two categories, but rather a spectrum that varies between the two extremes.

It is essential to consider your experience when deciding which method is best for you, as there are still limits to what science can tell us and each athlete can react differently (see the article below). I have personally experienced a situation where a professional player with many years of experience planned to use ice baths for recovery during the off-season, even though there may have been more effective methods such as meditation or water floating to stimulate adaptation and improve performance. However, we decided not to intervene to avoid disrupting his routine. When dealing with more experienced players, it is crucial to not only consider what to say but also when and how to say it.

If you are a young athlete looking to improve your performance, I recommend experimenting with different techniques, such as stretching, meditation, sauna, and ice baths (Versey, Halson, & Dawson, 2013). Happy recovery!

About the Author

Leandro serves as a Strength & Conditioning coach at Piatti Tennis Center. You can follow him on Instagram ( https://www.instagram.com/leandro_mosconi_/) or subscribe to his subtract (https://coachleandro.substack.com/)

References:

Versey, N.G., Halson, S.L., & Dawson, B.T. (2013). Water immersion recovery for athletes: effect on exercise performance and practical recommendations. Sports Med, 43(11), 1101-30

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shona-Halson/publication/237070099_Water_Immersion_Recovery_for_Athletes_Effect…